0.009856 m3: Between the Book, the Model, and the Built in the Vedute Collection of Three-Dimensional Manuscripts

16-03-2016

In maart verscheen in het vermaarde internationale tijdschrift ‘ARCHITECTURE AND CULTURE’ een interessante en uitvoerige beschouwing over Vedute, geschreven door Marian Macken getiteld: 0.009856 m3: Between the Book, the Model, and the Built in the Vedute Collection of Three-Dimensional Manuscripts.

Op dat moment was zij werkzaam voor het Department of Architecture, Xi’an Jiaotong–Liverpool University, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China. De manuscripten van o.m. Inge Bobbink, Dini Besems, MVRDV, Peter Wilson en Bas Princen worden uitvoerig belicht.

ABSTRACT

Housed within the library of Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, is the Vedute Collection. Founded in 1991 with the purpose of building a collection of three-dimensional objects that make visible and tangible the concept of space, the collection is made by those active within various spatial disciplines such as artists, architects, and designers. To be included in the collection, there is an imposed constraint: each contribution must have a fixed format, in closed form, of 44 X 32 X 7 centimeters. These objects form a library and are referred to as “three-dimensional manuscripts.” This essay positions the collection as an alternative space of information for spatial practice, which operates between the book and the model, as a medium and interpretation of representation and built space. The dimensions of the fixed format are derived from the book, yet the contents do not consist of written pages. Their three-dimensionality offers connections to the architectural model, yet they are named manuscripts. The points of intersection between these media and the Vedute Collection will be examined in reference to qualities and characteristics such as objecthood, scale, containment, exteriority, and interiority. Further, the essay discusses the nature of the collection, the library, and the series in spatial documentation, and these spaces as territories for spatial practice, between demarcations of discipline.

Architecture’s long history with printed media reflects an entwined relationship between the physicality of built work and the immaterial. The medium of the book, particularly through modernity, aided the dissemination, understanding, perception, and, eventually, conception of architecture. Beatriz Colomina argues that modern architecture only became modern with its engagement with the media,1 and therefore, twentieth-century publishing established the reader as a valid audience for architecture. Hence, the site of architectural production shifted to publications and exhibitions, establishing the book and the model as artifacts of architecture, with different and unique positions in reference to architectural representation, operating with different visual registers. The prominence of the non-built realm of architecture is referred to by Kester Rattenbury:

Architecture’s relationship with its representations is peculiar, powerful and absolutely critical. Architecture is driven by the belief in the nature of the real and the physical: the specific qualities of one thing – its material, form, arrangement, substance, detail – over another. It is absolutely rooted in the idea of “the thing itself”. Yet it is discussed, illustrated, explained – even defined – almost entirely through its representations.2

The process of architecture continuing to explore innovation through alternative spaces of information is ongoing. With this in mind, a zone of activity, which sits provocatively at the juncture where books and models come together, offers further development of the relationship between the audience and architectural space, one in which the audience continues to be the reader, rather than the viewer. One such interstitial practice is demonstrated by the Vedute Collection, housed within the library of Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.3

Founded in 1991 with the aim of lending new impetus to the discussion and thinking about space and architecture, the Vedute Foundation has built a collection of three-dimensional objects that make visible and tangible the concept of space.4 The collection is made by those active within various spatial disciplines, such as artists, architects, and designers, and includes works by Ben van Berkel, Raoul Bunschoten, Steven Holl, and Peter Wilson.5 To be included in the collection, there is an imposed constraint: each contribution must have a fixed format, in closed form, of 44 X 32 X 7 centimeters. These objects form a library and are referred to as “three-dimensional manuscripts.”6

The collection of over 200 works includes both individual acquisitions and themed sub-collections initiated by the Vedute Foundation, such as “The City Library of the Senses,” “The Written versus the Constructed,” and “00:00 Time & Duality.”7 The word veduta, from the Italian meaning a view, plural form vedute, refers to a realistic, detailed painting of a town scene with buildings of interest, as shown in the work of eighteenth-century Italian artists such as Canaletto and Piranesi.8 In the case of the Vedute Collection, the name refers to a quality of the collection given to each letter. For example, “V” stands for Verborgen/Verscholen, meaning hidden spaces; “E” for Eenheidsmaat, a custom-made suit of uniform size, unity in diversity; and “D” for Doos, or box, referring to their container.9

The three-dimensional manuscripts of the Vedute Collection have the format and form of books, and derive their dimensions from books. As Joost Meuwissen writes, “they stand or lie like a book on their bookshelf, they refer to a book, they remind me of a book, they are a book.”10 However, the contents do not consist of written pages involving a paginated sequence of reading. Although as a whole the collection is called a library, the Vedute Collection is not a collection of artists’ books,11 a genre with extensive and difficult-to-define limits. While many artists’ books function as sculpture or installation, referring to bookness more than to the physical elements of contained pages, the Vedute Foundation chooses not to use this term. Are these objects then models? It could be said that many operate as spatial representations, and are similar in size to many architectural models. Yet the contents of the collection are referred to as three-dimensional manuscripts.

This naming – not-books, not-models – then raises the question of territory and prompts the questions, “Is it a book? Is it a model? If not, then why?” However, these questions seem to demand definiteness and definition. Perhaps richer and more valuable questions are: What is offered to spatial practice and what is offered to representation by calling these works three-dimensional manuscripts? What does the format of the Vedute Collection offer different from the book and the model? This paper begins with a brief survey of the collection to outline common characteristics and themes, and positions the collection as an alternative space of information for spatial practice. While referring to the collection’s book-ness and model-ness, the collection is cast as representations, objects and artifacts, that are between books, models, and built space. In doing so, the collection offers methods of seeing space and techniques of working with space, and describes the threedimensional manuscript as a tool, process, and object that operates between demarcations of discipline, resulting in a cross-disciplinary library and archive.

The 44 32 X 7 Centimeter Object

In examining the Vedute Collection, one begins to notice certain tendencies or themes. The strongest of these, and the overarching feature of the works in the collection, is their shared format. It is an unusual library in that the distance between bookshelves may be consistent. The fixed format of the Vedute Collection defines a volume – 0.009856 m3 – for inclusion. This volume implies containment and numerous examples embrace this repository quality. In many works, components may be unpacked and arranged to create new forms, and then rearranged. With others, elements contained within unfurl to become bigger than their housing. The specific dimensions of the collection suggest a particular type of container, that of a suitcase, and some works interpret this as a form of receptacle. Hence, the notion of container is considered as both a physical entity and a conceptual program.

Through direct reference to the required dimensions, the influence of format as a design factor may be seen in many works in the collection. One such example is “Vierenveertig Bij Twee.ndertig Bij Zeven” by jewelry designer Dinie Besems, which is a small bag containing a silver jasseron chain. By suspending the chain in two hands, the outline of an object measuring 44 X 32 X 7 centimeters is formed (Figure 1). Rather than being a repository, the work itself momentarily becomes the full-scale space of containment.12 The strictly defined format also influences methods of working, as well as outcome. For example, Pieter Geraedts’s work creates the required volume through the solidity of paper. One day’s newspapers are shredded, pulverized, and mixed into pulp to be molded into a form of the exact required dimensions. With the basic assumption that forms affect sense, it is shown also to affect conception and process.

Such examples demonstrate works that refer to, and engage with, their own form. Karen Junod, writing in The Oxford Companion to the Book, begins her entry for artists’ books with the succinct sentence: “A medium of expression that creatively engages with the book, as both object and concept.”13 Similarly, these works may be defined as a media of expression in which content and operation are influenced by format: the collected works creatively refer to volume, form, and dimensions, as both an object and a concept. Just as artists’ books must in some way “acknowledge the medium through which they are communicated,”14 the content of each work in the Vedute Collection is inextricably linked to its form. This characteristic both defines the library of works and underpins their potential as a spatial expression different from, yet complementary to, other three-dimensional architectural representation.

The Book-Like and Model-Like Object

Works in the Vedute Collection display both book- and model-like qualities: the act of making a work for the collection is referred to by architect and contributor Andrew McNair as “writing architecture and building books.”15 Furthering this analogy is Alison Smithson’s reference to these related activities: “a book is like a small building for us.”16 Rather than interpreting the book as a building or the model as a book, a richer line of inquiry refers to the points of intersection between books and models and the comparative principles of operation between these media and the Vedute Collection. Examining the manuscripts’ bookand model-like qualities casts them as spatial media that carry and distribute information in a particular mode, and with potentiality for spatial imagining.

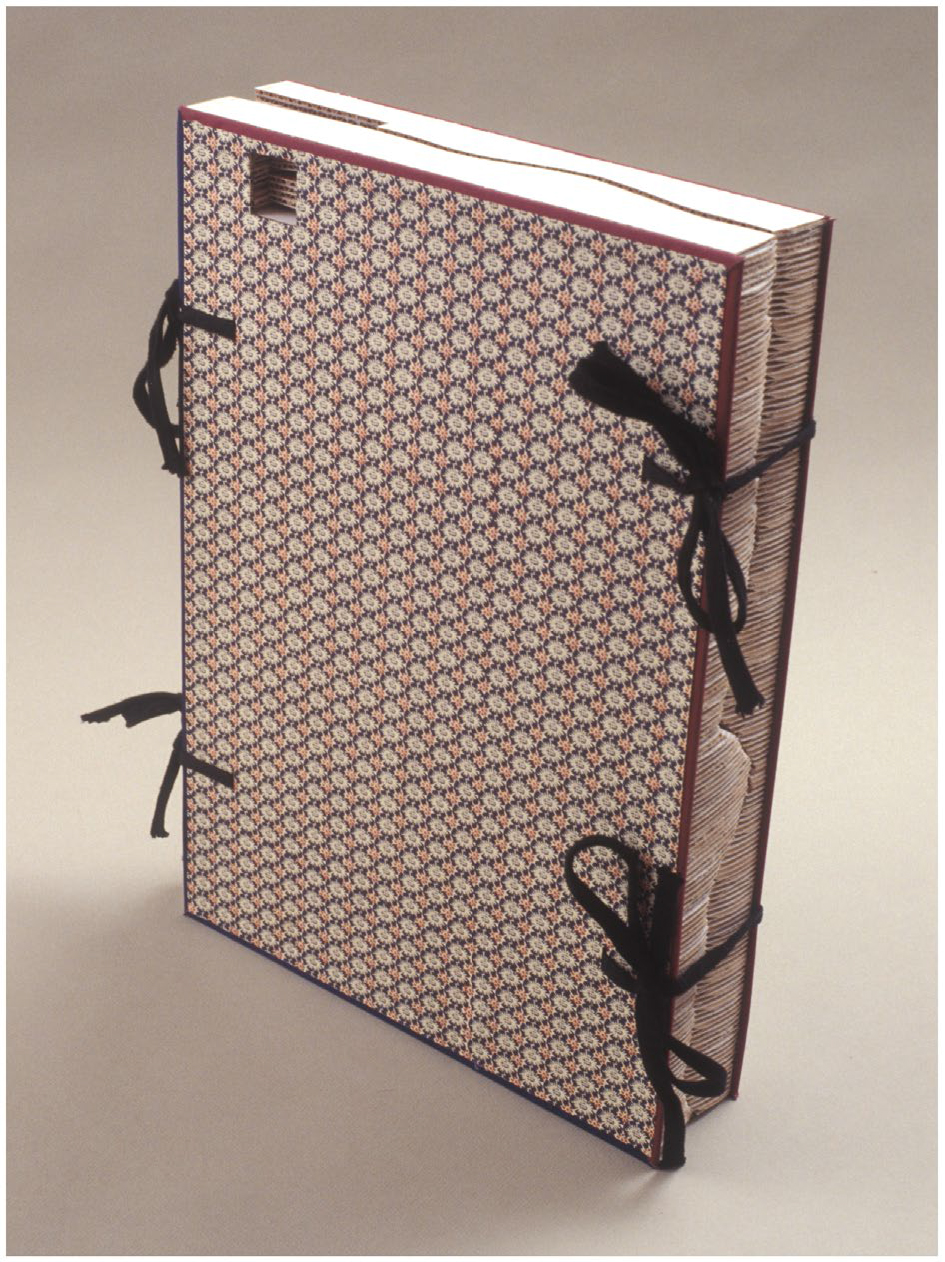

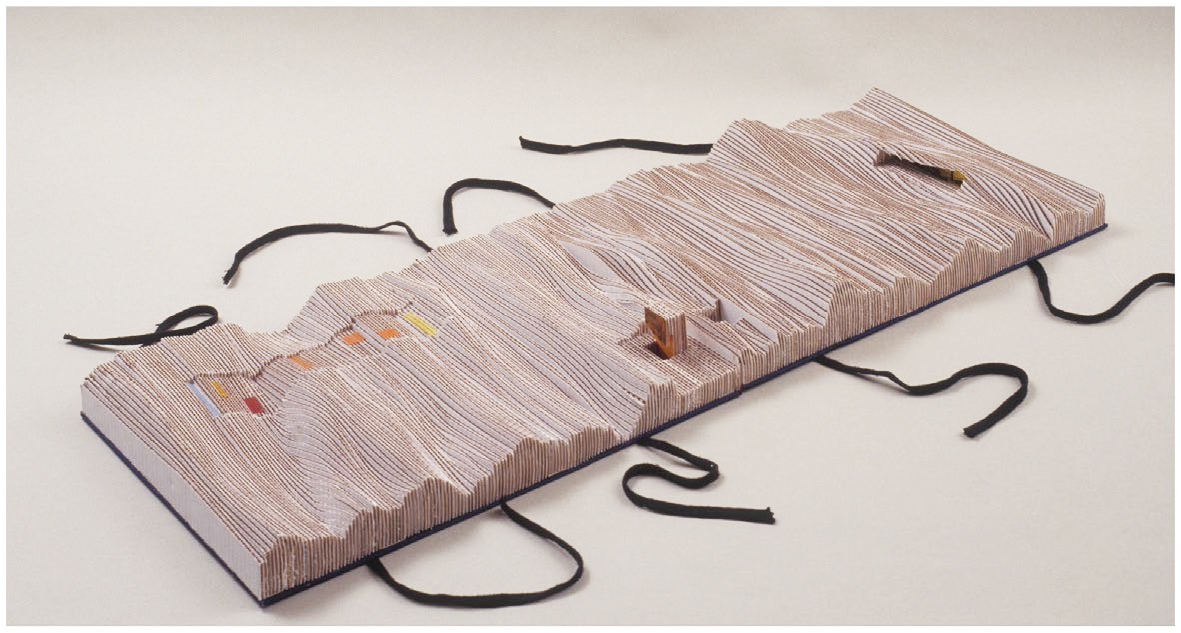

A shared characteristic that many of the works in the Vedute Collection display is their dual forms: closed and open. For example, “Schaalloos Gebonden,” by Inge Bobbink and Arthur Labree, outwardly resembles an historical book. When the cover is untied, it opens to reveal a corrugated topography of “endless stories in a space without scale”17 (Figures 2 and 3). Similarly, the plain wooden covers of “Entree Rvu” by MVRDV18 and Duzan Doepel open to a gently sinuous landscape of smoothly sanded grained timber (Figure 4). The reader is immersed within the revealed interiority of these works, which offer depth and volume as components of their making.

Similarly, the book is both a volume in space and possesses the ability to be opened. In her essay on scale within architectural drawings, Susan Hedges refers to Susan Stewart’s description of the book as offering metaphors of containment, of exteriority and interiority, of surface and depth, and of covering and exposure19: “The book sits below me closed and unread; it is an object, a set of surfaces. But opened, it seems revealed; its physical aspects give way to abstraction and a nexus of new temporalities.”20

As would be expected, many works make direct reference to the book, either to its form or to its role as a vehicle of information. The work by Steffen Maas, a graphic designer, is a book of blank pages. While a book’s design is usually a combination of various influences – paper selection, content, budget constraints, fabrication method – in this work it is the overall dimensions that are the main influence on the finished work. Maas worked with a bookbinder painstakingly to achieve the required exact thickness of seven centimeters.21 The paper is thin and the book includes a bookmark to allude to a linear textual reading of the work.22 On the white cover, gilt embossed, reads “44 X 32 X 7 cm In Closed Form” as title. The blank interiority of this work emphasizes the possibly infinite terrain of the (invisible) textual referent. Beyond the quality of its objecthood, the book is referenced in other ways; these include works that refer to the structure of the book and composition of accumulated pages, and its collective presence within libraries.

Examining the collection’s book-like qualities leads to the notion of text. The texts of many works in the collection are three-dimensional images, revealed as visual statements. Book scholar D.F. McKenzie defines the word “text” to extend beyond manuscripts and print to other forms, such as verbal, visual, and numeric data, archives of recorded sound, films, videos, and any computer-stored information.23 He goes on to write that the derivation of the word is from the Latin textere, “to weave,” and therefore “refers, not to any specific material as such, but to its woven state, the web or texture of the materials.”24 Therefore, it is the act of construction, not the presence of linguistic elements, that constitutes a text.25 This then allows for a shift, from text as a material medium to text as a conceptual system, “from the weaving of fabrics to the web of words,”26 or, in the case of the Vedute Collection, to the web of images and forms.

Some works refer to the space that text and letters create, using the word manuscript as inspiration. These works interpret the space of the alphabet, as both material and technique, which conceptually forms stories and produces endless permutations of spatial imagining. Italo Calvino writes, “The proper use of language is one that enables us to approach things (present or absent) with discretion, attention and caution, with respect for what things (present or absent) communicate without words.”27 This description identifies textual content as open to interpretation into other media, aligned with McKenzie’s definition. The content of the Vedute Collection makes manifest the connections between space and representation. McKenzie argues that “what constitutes a text is not the presence of linguistic elements but the act of construction” in creating a woven conceptual system.28 Calvino is equally concerned with text that is communicated between absence and presence, and the process of transmission. This process is articulated in the morphology of the manuscripts.

Often books are reduced to their linguistic text only, undermining the acknowledgement that they are a kind of totalizing sign system: the materiality of the book helps make its meaning.29 When books are reduced to just their texts, ignoring other components of the book – such as its paper, typeface, binding, cover, size – the reader is impoverished, promoting “a kind of illiteracy, because we forget about how to read.”30 This aspect of a book’s wholeness is emphasized by Johanna Drucker: “a book is an entity, to be reckoned with in its entirety.”31 It is in this respect that the Vedute Collection can be considered to be book-like: these are manuscripts that operate beyond the logical conventions of language printed on the flat page, and instead present an integrated design communicating the realm of intentions of their designers.

The book as object offers a stable format, as opposed to the alterability of digital formats. According to Drucker, the idea of the book, its form and function, is “the presentation of material to a fixed sequence which provides access to its contents (or ideas) through some stable arrangement.”32 The digital book is not bound to some particular physical substrate, but moves between media. The physical organization of the information is unimportant and the layout and typography can be changed if a copy is loaded into an editing program. William J. Mitchell argues that this illustrates a massive, fundamental shift that has taken place in the conditions under which artifacts – including works of architecture – are conceived, constructed, and consumed.33 It may be argued that through the digital interfaces we manufacture perception is now perpetually in a state of flux.34 The book is able to negotiate this by the very nature of its physical format; in this post-digital realm, its presentation of work of fixed format, scale, and binding emphasizes the materiality of the medium.

With this in mind, the text of the Vedute manuscripts is contained, determined, and stable. It is, of course, open to interpretation and changeable to some extent through the interaction of the reader. However, it is at once both fixed in time – the enduring present of its creation – yet temporally open, with every reading bringing new meaning and, hence, change. The book is not merely an object, but also the “product of human agency in complex and highly volatile contexts”;35 in this regard the manuscripts similarly perform. The audience of these manuscripts is readers: just as “a book only comes into being when it is read,”36 so too do these manuscripts demand interaction.

Many works in the collection resemble models, due to their size, materials, subject matter, and maker: readers approaching these works search for scale references. For example, Bob van Reeth’s “Zonder Titel” is a series of eight timber concentric rectangles that may be extended vertically to form a ziggurat, to achieve the maximum volume from the mass.37 Freed from scale restrictions, one speculates whether it could be read as a building, a piece of furniture, or as a full-scale object. Just as the model interprets the physical object as expressive form, the Vedute manuscripts demonstrate the manifestation of an idea with threedimensionality and substance. A model is an instrument within, and product of, a creative process. These works may be seen as fulfilling this role, however the intentions and motives of their making are different.

Both the book and the model possess a shared objecthood. They both occupy a volume in space and, simultaneously, refer to another conceptual terrain. The book exists as an object, and an interior that a reader can enter – the act of reading spatializes the structure of the book.38 As Andrew MacNair writes, to accompany his work “Spanish Haarlem Actual”: “A book is constructed thought composed of words and pictures written, printed, and bound into a compact volume of spaces becoming a world of its own looking into a deep interior and out to far horizons.”39 Models equally demonstrate this twinning of the 1:1 scale object with its to-scale referent. Christian Hubert writes that there is both a “deep desire to take our models for reality”40 and that the autonomous objecthood of the model is always an incomplete condition: “The model is always a model of.”41 Hence, books and models operate as a duality of material presence: as a sign of something else, and an autonomous project. Just as a book is “less and more than its contents alone,”42 each manuscript is a physical object, yet signifies something abstract. Similar to a book, each manuscript is a metonym for that which we read or “for the thoughts that we have as we read.”43

Between the Book and the Model

Although the works in the Vedute Collection display qualities similar to models and books, and operate analogously, they simultaneously embody a quality of not-ness: they are not-models and not-books. This nomenclatural separation allows these manuscripts to situate themselves between media, and occupy a different and capacious realm. Rosalind Krauss, in her seminal essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” writes of modern sculpture’s similar negativity, that by the early 1960s it had “entered a categorical no-man’s land,” as not-landscape and not-architecture.44 However, instead of sculpture being “the privileged middle term between two things that it isn’t,”45 rather it is only one term on “the periphery of a field in which there are other differently structured possibilities.”46 Similarly, rather than the Vedute manuscripts occupying “a kind of ontological absence” through a combination of exclusions, these “nots” provide the territory, an expanded field, for a practice which is not defined by the practices or conditions of a particular medium.47 Although still needing to be legitimized by spatial reference, the works in the Vedute Collection are neither proposing nor documenting space, nor do they correspond literally with the spaces made by their makers. They may detach themselves from, or renegotiate their relationship to, a built or unbuilt referent.

In this regard, the Vedute manuscripts embody the intentions of the 1976 exhibition “Idea as Model,” curated by Peter Eisenman: to present the model as having an artistic and conceptual existence independent of the project they represented. The exhibition aimed to prove that the model was a conceptual, rather than a narrative tool, on the “border between representation and actuality.”48 This exhibition and its accompanying catalogue shifted the notion of the building as the model’s referent, revising the potential territory of the architectural model.

Eisenman’s aim was to emphasize “the model’s capacity to render the unimagined visible and to provide space for the unexpected.”49 However, the questionable success of the exhibition’s ongoing legacy, of changing the model’s role, is evidenced by publications with the same intention, in the intervening thirty-five years.50 The model is still tethered to the question of what it “can embody and signify, once its essence is expanded beyond its purely representative character.”51 Though viewed neither solely as a discrete entity nor as a tool for creating a building, the model is still seen as an integral part of something larger: it remains as a member within a representational series.

In comparison, the Vedute spatial manuscripts achieve autonomy from the role of referent to a built work: they are not part of a series moving towards, or coming from, a built work. The termination of the lineage of architectural representation is predominantly a built project; the manuscripts extend and expand this lineage. By naming them differently, they expect an independent existence as an object and process. Maarten Kloos, in writing about the collection, states:

If it works, the manuscript is not a model, not a “shrunken big space,” not a ship in a bottle, but the gateway to a 1:1 experience. […] The entire collection […] is not a collection of images of reality, not a realistic reflection of reality and not a flight from reality. It can however, be regarded as an interpretation of reality in all its complexity. And more.52

An example of a work that employs model-making techniques, yet is not a surrogate for a building, is that by Peter Wilson, with Jim Yohe. “‘K’ Built and Written (2 Volumes)” takes up the space of two manuscripts on the shelf, being fourteen centimeters wide (Figures 5–7). A pink, blue, and brown flannel sheet wraps a plywood box, stamped with the letter “K” in red, and words beginning with “K” – kilo, kunst, K-value, kindergarten, Kafka, käse, klok. Like a drawer, out of this slides a large plywood “K” with hollow parts. Within the volume of the letter are interior spaces, inhabited by model-maker’s people. Wilson, in his text for the work, alludes to the symbolism of the letter as having no absolute scale, and no singular presence. By not being a model of something, the work refers to the oeuvre of the designer and his fascination with language: a dialogue between the written “K” – “words frame images” – and the built “K” – “buildings frame life.”53 This work proposes a model that may be opened and reveals an interior, yet in this act of interaction, provides a one-to-one experience to which Kloos refers.

Stefaan Vervoort writes that for the model to gain autonomous existence – as Eisenman intended – “would necessitate deserting the domain of architecture for that of sculpture, in which the object is no longer legitimized by its architectural reference.”54 The contents of the manuscripts are not architectural projects, they are not simply modeling built or unbuilt space, so therefore, it would seem, they are not architectural models. Rather than the binary options of either model or sculpture, a term that seems too broad, the collection offers an alternative: a representation that is three-dimensional and within the architectural domain. The Vedute works are representational strategies that situate themselves between models, sculpture, and instrument. Equally, these works separate themselves from the constraints of a book and its textual references:

When a bibliophile gets his hands on a book he uses all his senses: the weight, the size and the tangibility of the whole, the smell and the sound of the paper, the design of page and typeface, they all play a role in the ultimate appreciation. Books are sometimes particularly beautifully made, but the design is mainly subservient to the textual contents. The library of the Vedute Foundation shows us that there is another way.55

The Vedute Collection is book-like in that it is analytical and emphatically editorial, yet it is a reflection not just of the space we all occupy, but of the inner mind of the maker and their processes of working.

An example that assertively sets itself aside from the model and the book, yet works strongly between them, is “Boulak/Ca.ro” by artist Bas Princen. After a study trip to Egypt, photographing buildings in the Nile delta and the area around Cairo, he discovered he had photographed a building that closely resembled the proportions of the Vedute format. In calculating the building volume, he realized that it was approximately one hundred times the dimensions of the manuscript requirements.56 The negative was then printed so that the building in the photograph measures 44 X 32 X 7 centimeters (Figure 8). This work, architectural in its content, poetically engages with the constructions of orthographic representation and printed media. Princen correlates the operations of the model and the book through an architectural understanding of scale and the medium of photography.

“Boulak/Caïro” perceives and engages with representation as an act of translation and transformation. Patrick Healy, in The Model and its Architecture, writes that models have tendencies to “inform, translate, and argue.”57 Rather than representation being seen as a repository for a complete idea of a building, “Boulak/Ca.ro” perceives it as an act of translation. Mark Wigley writes that translation is not the transference, reproduction, or image of an original. Rather, the “original only survives translation. The translation constitutes the original it is added to.”58 To focus on the act of translation and transformation inherent within representation as the transition between forms highlights the role of interpretation: “interpretation has a role even more crucial than that of asserting architecture’s authority. Interpretation and design coalesce.”59 This description sees translation as giving voice to the intention of the work, not through reproduction but rather as supplement. It is this role of the manuscript as a transitional hyphen between forms that highlights its potential as a spatial practice and as a space of information.

The Spatial Manuscript

For the works in the Vedute Collection, it is the act of viewing, or reading, that sets them apart from models. The materiality of these artifacts – including beeswax, seawater, birdseed – invites the hand of the reader to understand and interpret them. Additionally, many works tend to act as devices or machines, driven by the reader. The tactility of the works reinvigorates and “redeem[s] the object in the face of its supposed dematerialization by conceptual art.”60 Just at the power of the book lies in its ability to create conditions for reading,61 so too do the Vedute works establish the relationship between author and reader.

To visit the Vedute Collection, one leaves the public ground floor of the institute and climbs the stairs to a quieter library space. The objects need to be requested for viewing, and one waits for their arrival to be wheeled in on a trolley. Each sits within a cardboard case, or its own covering, and needs to be unpacked and opened. This is an event that takes time, and may be done ceremonially: this is an event in which one participates. We, as readers, operate these manuscripts: “they reveal their essence through use.”62 We are not just looking into a box of objects, we are opening, unfolding, unpacking, revealing, moving, rearranging, handling, contemplating, and then repacking and closing: we are doing.

The breadth of the collection now offers another space, beyond each manuscript’s spatial reference: the space of, and within, the collection itself. A collection offers an antithesis to the uniqueness of each work. The imposed constraint of a common volume or format allows for a point of comparison between works. As demonstrated, the uniqueness of each work in the collection is inevitable, but the common format allows each work to interact with its neighbor and with its surroundings. It is a library that asks authors to take into account those manuscripts that sit beside theirs on the shelves and in the collection. Therefore, the collection may be seen as a medium: comparisons may be made between works. Since these manuscripts also involve readers, the collection provides a framework that investigates and positions the public as a medium between the objects.63

This is a collection that is often exhibited. The architecture exhibition has traditionally aimed to be either a substitute for the experience of visiting the building or city displayed, or display the architect’s methodology of thought and design process. Integral to these aims is the notion of the documentation of architecture through exhibition. There is a conventional display hierarchy of architecture of sketch, plan, and model produced during the design process, shown with the post-construction photograph. These are presumed to present architecture, writes Andrew Benjamin.64 In architectural exhibitions, the three-dimensional object – the model – has traditionally been included as it is seen as more accessible due to its legibility, three-dimensionality, and claims of objectivity. The exhibition of the Vedute Collection does not rely on the building as referent; rather, it is a discrete investigation into spatial practice. Instead of being a simulation or representation of a particular building, the exhibition is a space of integrity separate from the displays of the byproducts of architecture’s design process.

The size of each work within the Vedute Collection is scaled to sit on a tabletop, close to the reader: engaging with these works is a solitary, intimate experience. In opposition to an exhibition of models, the Vedute Collection is concerned with revealing, opening, and containing: these works hold an interior. Due to these aspects, an exhibition of Vedute works, especially those that strongly invoke the repository quality of curated, composed objects, is reminiscent of Wunderkammer, or a cabinet of curiosities, a phenomenon that arose in Renaissance Europe to display assemblies of objects, often relating to natural history. These cabinets demonstrated and catalogued the interests and passions of the curator, displaying the exotic and scientific.

As part of the 13th International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Biennale, 2012 curated by David Chipperfield on the theme of “Common Ground,” Todd Williams and Billie Tsien invited thirty-five friends – architects, designers, writers, craftsmen, curators, artists – to fill a box with things that inspire them. Each box, made by Stephen Iino and measuring approximately 50 X 101 X 30 centimeters, became both the system of shipping and the site for each cabinet of curiosity.

Some contributors interpreted this as an assemblage of objects lying close to hand; others made new objects to be included, such as Will Bruder’s “304 Wood Stakes+,” which inserts a repeated form with variation to create an internal spatial collage.

These Wunderkammern are deeply personal statements and recall the contained compositions of Joseph Cornell. Each object is entrancing in itself – as Williams and Tsien write, architects are “almost always ‘thing’ people, curious and engaged in the physical world. As much as we use digital tools, we still crave things to touch”65 – yet from these objects, the viewer tries to understand and learn the personalities of the contributors.66

For the Biennale exhibition, the returned boxes were installed on shelves in Casa Scaffali, a small shed formerly used to house seeds and gardening equipment, in Giardini della Virgine. As each box became an individual cabinet, so too did the building for the curators:

We chose to think of Casa Scaffali as our shared box. We filled the box with: people who were out teachers and mentors, and people we taught and mentored, people for whom we worked, and people who worked for us, people who inspire us, people who amaze us, people we love, friends. That is what is in our box.67

When exhibited collectively, the repository quality of the Vedute works offer individual and multiple volumes of presence. The usual display of architecture in exhibitions presents images of matter, rather than the work of matter.68 This then leads to the question of how matter’s presence can be exhibited “if the centrality of the image – the reduction of matter to its image – is to be distanced and matter reinscribed both as the production of the architectural effect and therefore as the subject to be displayed?”69 Rather than subordinating matter to its image, material presence as the object of display allows meaning to be repositioned. Interpreting the works of the Vedute Collection as the presence of matter offers the opportunity for an exhibition to be read. The act of reading allows the conjunction of the imaginary world of the text with the present tense of the reader. According to Paul Ricoeur, reading then “becomes a place, itself unreal, where reflection takes a pause.”70 Just as a book “contains both its reader and its author,”71 the Vedute exhibition offers multiple spaces of containment: reading becomes a medium that one crosses through, and is immersed within, in encountering the collective volumes of the manuscripts. The manuscripts flatten the hierarchy between author and reader and provide a space within which the “the roles of the two evolve to accommodate new expectations and needs.”72

The word “manuscript” refers to the stage in which a work exists before being published, before the act of reproduction. It is the precondition, before multitudes of copies exist. In this way, a manuscript drives the act of reproduction and is the original from which copies are made. Original, not in the sense of uniqueness, but rather sequentially, as a chronological order of working. The Vedute’s three-dimensional manuscripts demonstrate a method of seeing space, a technique of working, and a format of making. These not-books, not-models, are a provocation and a trigger for future perceptions and production. As spatial manuscripts, they can be seen as original, as beginning a new trajectory of conceptual thinking about space, for the contributor and for the reader. They are spatial manuscripts of experimentation and a rich territory for future practice.

Conclusions: The Spatial Reader

Representations always work in relation to other representations, of a kindred or opposing sort.73 The manuscripts of the Vedute Collection create a point of intersection between books, architectural models, and built space. They propose a different yet related medium to expand spatial discourse. Krauss’s notion of the “post-medium condition” highlights work that operates between, among, within, and beside traditionally discrete and identifiable media.74 It is this intention that drives the three-dimensional manuscripts of the Vedute Collection: to run parallel, and intersect, with books, models, and built space.

The specificity of the fixed dimensions means that each work is both a container and the contained, both perimeter and volume. Each work opens to reveal its interior and asks the reader to participate in its unpacking. The volumetric and thematic cohesion of the library of manuscripts, due to the limits and boundaries of the collection, are a bound collection of ideas, bound in the sense of relating closely, rather than referring to a structure of format. As a collection they propose a library, and archive, of constructed understandings, displaying materiality and tactility. The manuscripts offer a method of seeing space, a technique of working with space and a format of making space. This alternative, complementary space of communication – both a repository and method of practice – demonstrates the significance of, and possibilities for, spatial investigation.

Notes

1 Beatriz Colomina, Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), 14.

2 Kester Rattenbury (ed.), This is Not Architecture: Media Constructions (London: Routledge, 2002), xxi.

3 Vedute Foundation, http://www.vedute.nl/over/index. php?lang=en (accessed January 14, 2015).

4 A City Library of the Senses, translated by Donald Gardner (Amsterdam: Stiching Vedute, 1996), 38.

5 The collection was founded by Rob Bloem, Christian Bouma, Mariska van der Burgt, Peter de Rijk, and Suzanne Styhler, and was housed, for part of its history, at NAI, Amsterdam.

6 See note 3.

7 Ibid.

8 Oxford English Dictionary Online (Oxford University Press), http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/221846 (accessed January 14, 2015).

9 The other letters refer to “U”: uniqueness of each copy, and unpacking, unfolding; “T”: Teken or sign; and “E”: Eerste inspiratie, initial inspiration; Mirjam Ijsseling, “Foreword.” In Kijk op Verdute/ Views on Vedute, edited by Arets Weil, Willem Koerse, Maarten Kloos, and Joost Meuwissen, translated by Michael O’Laughlin (Amsterdam: Stiching Vedute, 1996), 6.

10 Joost Meuwissen at the opening of the exhibition at the Berlage Institute in 1994, cited in Weil et al., Kijk op Verdute/ Views on Vedute, 32.

11 As stated by Meuwissen; ibid.

12 See note 3.

13 Karen Junod, in The Oxford Companion to the Book, edited by Michael Suarez and H.R. Woudhuysen (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 484.

14 Annabel Fraser, “Exploring Books: What is a Book and What it is Not.” Communication Art and Design thesis, Royal College of Art, 2007, 6.

15 Andrew MacNair, “Building Book,” in The Written Versus the Constructed, (Amsterdam: Stiching Vedute, 1998), 17–21 (on 18).

16 Alison Smithson, quoted by Peter Smithson, in “Think of it as a Farm!: Exhibitions, Books, Buildings, An interview with Peter Smithson,” in Rattenbury, This is Not Architecture, 97.

17 Inge Bobbink and Arthur Labree, Vedute Foundation, http://www.vedute.nl/vedutes/ documenten/0073.php?lang=en (accessed January 14, 2015).

18 Winy Maas, Jacob van Rijs, and Nathalie de Vries.

19 Susan Hedges, “Scale as the Representation of an Idea, the Dream of Architecture and the Unravelling of a Surface,” Interstices: Journal of Architecture and Related Arts: The Traction of Drawing, no. 11 (2010): 72–81 (on 77).

20 Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 37, quoted in Hedges, “Scale as the Representation of an Idea,” 75.

21 See note 3.

22 Ibid.

23 D.F. McKenzie, Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 13.

24 Ibid..

25 Ibid., 43.

26 D.F. McKenzie, “The Book as an Expressive Form,” in The Book History Reader, edited by David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery (London: Routledge, 2006), 37.

27 Italo Calvino, Six Memos for the Next Millennium, quoted by Peter Wilson in The Written Versus the Constructed (Amsterdam: Stiching Vedute, 1998), 24.

28 McKenzie, Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts, 43.

29 Michael Suarez, “Oxford Companion to the Book: Michael Suarez S.J. in Conversation with Romona Koval,” The Book Show, ABC Radio National, July 16, 2010, http://www.abc.net.au/rn/bookshow/ stories/2010/2955487.htm (accessed May 25, 2011).

30 Ibid.

31 Johanna Drucker, The Century of Artists’ Books (New York: Granary, 2004), 122.

32 Ibid., 122f.

33 William J. Mitchell, “Antitectonics: The Poetics of Virtuality,” in The Virtual Dimension: Architecture, Representation, and Crash Culture, edited by John Beckmann (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998), 206.

34 Asymptote, cited in Beckmann, Virtual Dimension, 288.

35 McKenzie, Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts, 4.

36 Yusuke Minami, “Fukuda Naoyo: Kaibun and Art,” in Artist File 2010: The NACT Annual Show of Contemporary Art: 018 Fukuda Naoyo. Exhibition catalogue (Tokyo: National Art Center, 2010), 6.

37 See note 3.

38 For further reference to this, see Marian Macken, “Binding Architecture: Drawing in the Book,” Architecture and Culture, 2, no. 2 (2014): 235–6.

39 Andrew MacNair, “Spanish Haarlem Actual,” in Vedute Foundation, http://www.vedute.nl/vedutes/ documenten/0085.php?lang=en (accessed January 14, 2015).

40 Christian Hubert, “‘The Ruins of Representation’ Revisited,” OASE, 84: Models: The Idea, the Imagination, the Visionary, edited by Anne Holtrop, Job Floris, and Hans Teerds, guest edited by Bas Princen and Krijn de Koning: 19.

41 Christian Hubert, in Kenneth Frampton and Silvia Kolbowski, Idea as Model (New York: Rizzoli, 1981), 17.

42 Brian Cummings, “The Book as Symbol,” in The Book: A Global History, edited by Michael F. Suarez and H.R. Woudhuysen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 93, in reference to books.

43 Ibid.

44 Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field, ” October, 8 (1979): 30–44 (on 36).

45 Ibid., 38.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid., 37–8.

48 Hubert, in Frampton and Kolbowski, Idea as Model, 17.

49 Editorial, OASE, 84 (2011): 21.

50 For example, ibid., 20–26.

51 Ibid., 20.

52 Maarten Kloos, “Magic Boxes: The Secrets of Vedute,” in Weil et al., Kijk op Verdute/Views on Vedute, 29.

53 See note 3.

54 Stefaan Vervoort, “The Modus Operandi of the Model,” in OASE, 84: Models: The Idea, the Imagination, the Visionary, edited by Anne Holtrop, Job Floris, and Hans Teerds, guest edited by Bas Princen and Krijn de Koning: 75–81 (on 75).

55 Ijsseling, “Foreword,” 1.

56 See note 3.

57 Patrick Healy, The Model and its Architecture (Rotterdam: 010, 2008), 53.

58 Mark Wigley, “The Translation of Architecture, the Production of Babel,” Assemblage, 8 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), 8.

59 Adrian Snodgrass and Richard Coyne, Interpretation in Architecture: Design as a Way of Thinking (London: Routledge, 2006), 3–4.

60 Antony Hudek, “Introduction: Detours of Objects,” in The Object, edited by Antony Hudek (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014), 20.

61 Ulises Carri.n, in Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook, edited by Joan Lyons (Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop, 1985), 31.

62 Ronald van Tienhoven, in Vedute Foundation (see note 3),

63 Ariane Lourie Harrison, in reference to exhibitions. Aaron Levy and William Menking, Four Conversations on the Architecture of Discourse (London: Architectural Association, 2012), 68.

64 Andrew Benjamin, “On Display: The Exhibition of Architecture,” in Flicker, edited by Hitoshi Abe (Tokyo: Toto Shuppan, 2005), 108.

65 Todd Williams and Billie Tsien, Wunderkammer (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013), 16.

66 Ibid., 10.

67 Ibid., 24.

68 Benjamin, in Abe, Flicker, 108.

69 Ibid.

70 Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, Vol. 3 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985/1990), 179.

71 Cummings, “Book as Symbol,” 93.

72 Bob Stein, “Social Reading is No Longer an Oxymoron,” in The Unbound Book, edited by Joost Kircz and Adriaan van der Weel (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2013), 45–56 (on 51–2).

73 Eve Blau, and Edward Kaufman (eds), Architecture and Its Image: Four Centuries of Architectural Representation: Works from the Collection of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), 13.

74 Roslind Krauss, ‘A Voyage to the North Sea’: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition (London: Thames & Hudson, 1999), 7, cited in Hudek, “Introduction: Detours of Objects,” 19.

References

– A City Library of the Senses. 1996. translated by Donald Gardner. Amsterdam: Stiching Vedute.

– Beckmann, John (ed.). 1998. The Virtual Dimension: Architecture, Representation, and Crash Culture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

– Benjamin, Andrew. 2005. “On Display: The Exhibition of Architecture.” In Flicker, edited by Hitoshi Abe, 108. Tokyo: Toto Shuppan.

– Blau, Eve, and Kaufman, Edward (eds.). 1989. Architecture and Its Image: Four Centuries of Architectural Representation: Works from the Collection of the Canadian Centre for Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

– Colomina, Beatriz 1994. Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

– Cummings, Brian 2013. “The Book as Symbol.” In The Book: A Global History, edited by Michael F. Suarez and H. R. Woudhuysen, 93–96. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

– Drucker, Johanna 2004. The Century of Artists’ Books. New York, NY: Granary.

– Editorial. 2011. OASE, 84: Models: The Idea, the Imagination, the Visionary, edited by Anne Holtrop, Job Floris, and Hans Teerds, guest edited by Bas Princen and Krijn de Koning, 20–26.

– Frampton, Kenneth, and Kolbowski, Silvia 1981. Idea as Model. New York, NY: Rizzoli.

– Fraser, Annabel. 2007. “Exploring Books: What is a Book and What it is Not.” Communication Art and Design thesis, Royal College of Art.

– Healy, Patrick. 2008. The Model and its Architecture. Rotterdam: 010.

– Hedges, Susan. 2010. “Scale as the Representation of an Idea, the Dream of Architecture and the Unravelling of a Surface.” Interstices: Journal of Architecture and Related Arts: The Traction of Drawing, no. 11: 72–81.

– Hubert, Christian. 2011. “‘The Ruins of Representation’ Revisited.” OASE, 84: Models: The Idea, the Imagination, the Visionary, edited by Anne Holtrop, Job Floris, and Hans Teerds, guest edited by Bas Princen and Krijn de Koning, 11–25.

– Hudek, Antony (ed.). 2014. The Object. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. – Hudek, Antony 2014. “Introduction: Detours of Objects.” In The Object, edited by Antony Hudek. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 20.

– Ijsseling, Mirjam 1996. “Foreword.” In Kijk op Verdute/Views on Vedute, edited by Arets Weil, Willem Koerse, Maarten Kloos, and Joost Meuwissen, translated by Michael O’Laughlin, 1–3. Amsterdam: Stiching Vedute.

– Junod, Karen 2010. “Artists’ Books.” In The Oxford Companion to the Book, edited by Michael Suarez and H.R. Woudhuysen. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 484.

– Kloos, Maarten 1996. “Magic Boxes: The Secrets of Vedute.” In Kijk op Verdute/ Views on Vedute, edited by Arets Weil, Willem Koerse, Maarten Kloos, and Joost Meuwissen, translated by Michael O’Laughlin, 12–30. Amsterdam: Stiching Vedute.

– Krauss, Roslind 1979. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” October, 8: 30–44.

– Krauss, Roslind 1999. ‘A Voyage to the North Sea’: Art in the Age of the Post- Medium Condition. London: Thames & Hudson.

– Levy, Aaron, and Menking, William 2012. Four Conversations on the Architecture of Discourse. London: Architectural Association.

– Lyons, Joan (ed.). 1985. Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook. Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop.

– Macken, Marian 2014. “Binding Architecture: Drawing in the Book.” Architecture and Culture, 2, no. 1: 225–44.

– MacNair, Andrew 1998. “Building Book.” In The Written Versus the Constructed, 17–21. Amsterdam: Stiching Vedute.

– McKenzie, D. F. 2006. “The Book as an Expressive Form.” In The Book History Reader, edited by David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery, 35–46. London: Rutledge.

– McKenzie, D. F. 1999. Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

– Minami, Yusuke. 2010. “Fukuda Naoyo: Kaibun and Art.” in Artist File 2010: The NACT Annual Show of Contemporary Art: 018 Fukuda Naoyo. Exhibition catalogue (Tokyo: National Art Center), 6.

– Mitchell, William J. 1998. “Antitectonics: The Poetics of Virtuality.” In The Virtual Dimension: Architecture, Representation, and Crash Culture, edited by John Beckmann, 205–217. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press.

– Rattenbury, Kester (ed.). 2002. This is Not Architecture: Media Constructions. London: Rutledge.

– Ricoeur, Paul. 1985/1990. Time and Narrative, Vol. 3. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

– Snodgrass, Adrian, and Coyne, Richard 2006. Interpretation in Architecture: Design as a Way of Thinking. London: Rutledge.

– Stein, Bob 2013. “Social Reading is No Longer an Oxymoron.” In The Unbound Book, edited by Joost Kircz and Adriaan van der Weel, 45–56. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

– Stewart, Susan 1993. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

– Suarez, Michael, and Woudhuysen, H. R. (eds.). 2010. The Oxford Companion to the Book. Oxford and New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

– The Written Versus the Constructed. 1998. Amsterdam: Stiching Vedute.

– Vervoort, Stefaan. 2011. “The Modus Operandi of the Model.” In OASE, 84: Models: The Idea, the Imagination, the Visionary, edited by Anne Holtrop, Job Floris, and Hans Teerds, guest edited by Bas Princen and Krijn de Koning: 75–81.

– Wigley, Mark. 1989. “The Translation of Architecture, the Production of Babel.” Assemblage, 8: 6–21. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

– Williams, Todd, and Tsien, Billie 2013. Wunderkammer. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press.

Dinie Besems, Vierenveertig Bij Tweeëndertig Bij Zeven, 1997. Vedute Collection. Photo: Collection Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, on loan from Stichting Vedute/Vedute Foundation.

Inge Bobbink and Arthur Labree, Schaalloos Gebonden, 1996. Vedute Collection. Photo: Collection Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, on loan from Stichting Vedute/Vedute Foundation.

Inge Bobbink and Arthur Labree, Schaalloos Gebonden, 1996. Vedute Collection. Photo: Collection Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, on loan from Stichting Vedute/Vedute Foundation.

Inge Bobbink and Arthur Labree, Schaalloos Gebonden, 1996. Vedute Collection. Photo: Collection Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, on loan from Stichting Vedute/Vedute Foundation.

Peter Wilson with Jim Yohe, “K” Built and Written (2 Volumes), 1996. Vedute Collection. Photo: Collection Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, on loan from Stichting Vedute/Vedute Foundation.

Peter Wilson with Jim Yohe, “K” Built and Written (2 Volumes), 1996. Vedute Collection. Photo: author.

Peter Wilson with Jim Yohe, “K” Built and Written (2 Volumes), 1996. Vedute Collection. Photo: author.

Bas Princen, Boulak/ Caïro, 2009. Vedute Collection. Photo: Collection Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, on loan from Stichting Vedute/Vedute Foundation.